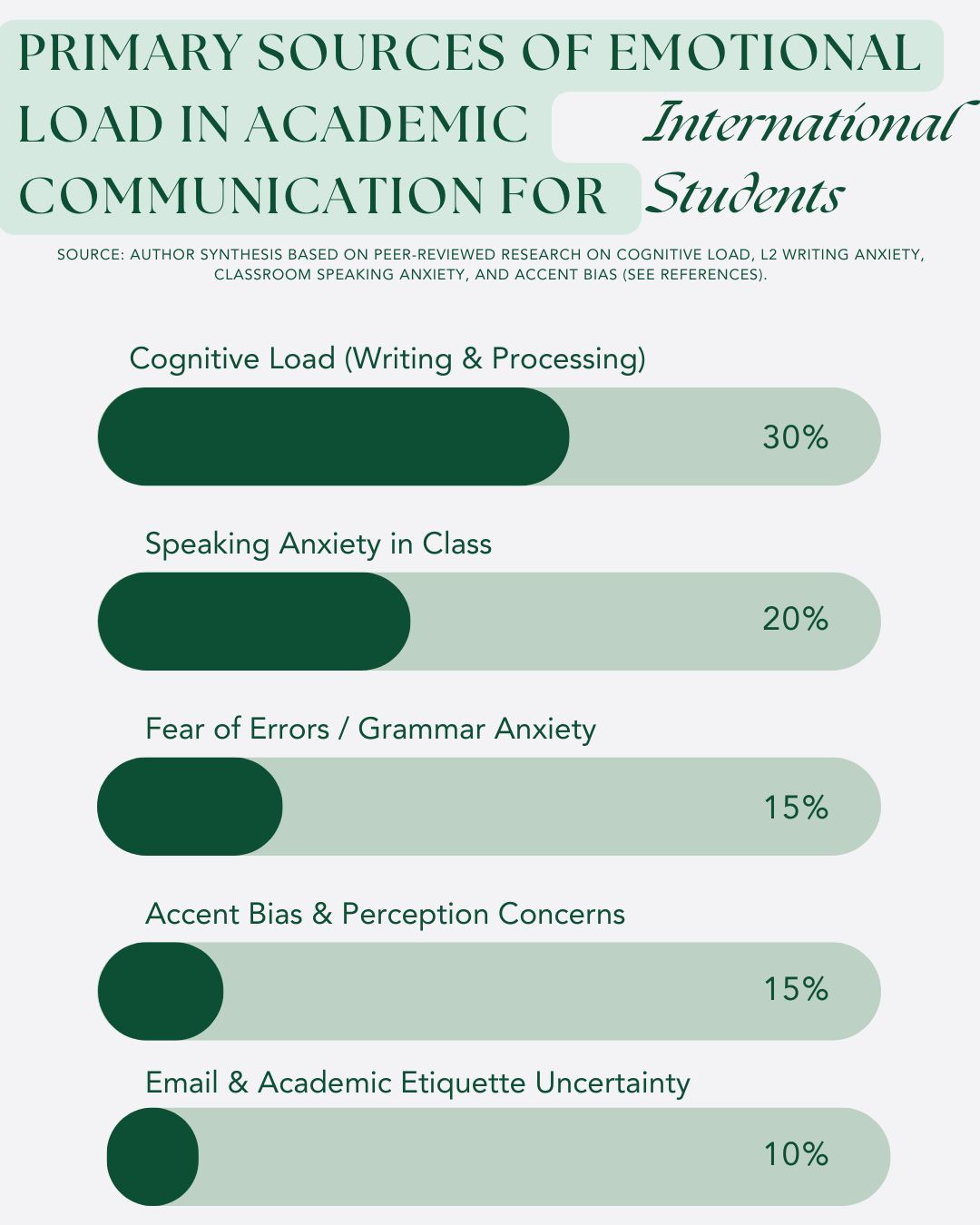

The emotional load of academic communication hits you in ways no language test prepares you for. You passed the IELTS or TOEFL. You got accepted. You assumed the hard part was over. Then you sat down to write your first email to a professor and froze. Email anxiety affects many students, but international students face additional uncertainty about tone and etiquette. You walked into your first seminar and stayed silent. Studies show that classroom silence often stems from anxiety rather than disengagement. You joined a group project and felt invisible. International students in multinational teams often struggle with language barriers and different working styles.

This is not a personal failing. Research confirms what many of us feel: academic anxiety, speaking anxiety in college, and ESL classroom stress create psychological burdens that native speakers simply do not carry. Understanding this burden is the first step toward managing it.

The Hidden Mental Weight of Academic English

Every sentence you write or speak in English requires decisions that native speakers make automatically. Word choice. Sentence structure. Tone. Academic conventions. Your brain runs constant background checks: Is this phrase too informal? Did I use the right preposition? Will this sound stupid?

Researchers call this process cognitive load. When you write in your first language you retrieve words and structures automatically but when you write in your second language you must consciously control each retrieval. This overloads working memory and leaves fewer mental resources for higher-level thinking like analysis and argumentation.

Language fatigue is real. Thinking in English all day creates mental exhaustion that compounds over weeks and months. By evening, many international students report feeling drained in ways their domestic peers do not understand. Your brain has been running a background translation program since breakfast.

The emotional consequences follow. Studies show that second language writers experience heightened fear of errors and stress about conveying ideas precisely. Grammar anxiety in college affects both your writing and your willingness to participate in class. The mental fatigue of constant translation becomes another weight on top of cultural adjustment.

Many students describe imposter syndrome. You know you earned your place. But when you cannot express your ideas fluently, you start feeling behind in college. ESL confidence issues feed a cycle: the less confident you feel, the less you participate, and the less you participate, the less confident you become.

Writing Papers in English

Writing essays in English as a second language presents specific challenges that go beyond vocabulary. ESL academic writing challenges include unfamiliar citation styles, different expectations for argument structure, and conventions that vary by discipline.

Research quantifies the gap. One study found that international students with strong English test scores still read at roughly half the speed of native speakers. They understood less of what they read and summarized it less effectively in writing.

This slower pace creates a productivity paradox. A paper your classmates draft in a weekend might consume your entire week. Time spent wrestling with grammar is time not spent on original thinking. Your best ideas may never make it onto the page because you ran out of energy converting them into acceptable English.

Writing directly in English helps. Research shows that drafting in your native language and then translating increases mental effort and produces lower-quality writing. Thinking in English from the start, even if it feels harder initially, frees up cognitive resources for content and structure.

Writing center help for international students can make a significant difference because centers that understand the specific needs of multilingual writers address both grammar anxiety and broader confusion about academic expectations. To find your campus writing center you can search your university website for "writing center" or "academic support services" and look for links under student resources or the library. Most centers are located in libraries or student success buildings and offer both in-person and online appointments. Many universities use online booking systems where you can schedule a session and specify that English is not your first language so they can match you with a tutor experienced in working with multilingual students. Some centers offer recurring appointments specifically for international students so ask about this option when you first visit. Use these services early in the semester before you fall behind because appointment slots fill quickly and building a relationship with a tutor takes time.

Speaking Anxiety in Class

Fear of speaking English in class keeps many international students silent. You need time to formulate a response, translate it internally, and check it for errors. By the time you are ready, the conversation has moved on. Your silence gets interpreted as disengagement rather than processing.

Group work anxiety adds another layer. International students in group projects often feel invisible or sidelined. Native speakers talk faster, interrupt more easily, and may not wait for you to gather your thoughts. The social dynamics of collaboration favor those who can think out loud in real time.

Confidence speaking English grows with practice, but only if you create opportunities for low-stakes practice. Record yourself answering potential discussion questions before seminars. Join study groups where you can rehearse ideas before presenting them formally. The goal is to reduce the processing time between thinking and speaking.

Some practical scripts help. When you need more time in a discussion, try: "That's an interesting point. Let me think about that for a moment." When you want to contribute but need to organize your thoughts: "I'd like to add something. Can I come back to this in a minute?" These phrases buy you processing time without signaling weakness.

Accent Bias and Discrimination

Accent discrimination in college is documented and real. Studies show that listeners judge accented speakers as less competent, less intelligent, and less credible, even when the content is identical. Accent bias in the classroom affects how professors and peers perceive your contributions.

This bias is unfair. But knowing it exists helps you understand that negative reactions may reflect prejudice rather than your actual abilities. Confidence speaking English with an accent requires accepting that your accent is not a flaw. It is evidence that you speak multiple languages.

Some students try to eliminate their accents entirely. This is usually unnecessary and often impossible. A more realistic goal is clarity. Slow down slightly. Emphasize key words. Pause between ideas. These adjustments improve comprehension without requiring you to sound like a native speaker.

When you encounter bias, you have choices. You can address it directly: "I notice I sometimes get interrupted. I'd appreciate the chance to finish my thought." You can seek allies who will amplify your contributions. Or you can focus your energy on written work where accent bias does not apply.

Emailing Professors

Email anxiety affects many international students because academic email etiquette varies by culture and the rules are rarely taught explicitly. You may find yourself wondering whether you sound too formal or too casual or too demanding or too passive.

A basic email structure works for most situations and reduces the stress of starting from scratch. Use a clear subject line that includes your course name and topic so the professor knows what to expect before opening your message. Open with "Dear Professor" followed by their last name and introduce yourself by stating your name and which class you are in before moving directly to your purpose. Add one or two sentences of context if needed and close with a brief thank you followed by your name.

Professors receive dozens of emails daily so keeping yours short and focused increases the chance of a helpful response. Ask one question at a time and proofread before sending without agonizing over perfection since a small grammatical error matters far less than clarity and politeness.

For office hours you might write that you would like to visit to discuss a specific topic and ask whether a particular day works or if another time would be better. For deadline concerns you can explain that you are working on the assignment and want to confirm your understanding of a specific requirement before proceeding. For grade questions you might mention that you reviewed your feedback and would appreciate the opportunity to discuss how you can improve in future assignments.

Having a starting template will not cover every situation but it reduces the anxiety of staring at a blank email wondering where to begin and how to strike the right tone.

Building Support and Confidence

Support for international students exists on most campuses, but you have to seek it out. ESL academic support services include writing centers, conversation partner programs, and academic coaching. Peer mentorship programs improve retention and grades for international students.

Connecting with other multilingual students reduces isolation and normalizes your experience. When you hear others describe the same frustrations, you realize you are facing a structural challenge, not a personal deficiency.

To improve academic English confidence, focus on progress rather than perfection. Track your improvements over months, not days. Celebrate small wins: a successful office hours visit, a paper that required fewer revisions, a comment that landed well in class.

ESL communication tips that help: Read extensively in your discipline to build automatic vocabulary. Practice speaking before high-stakes situations. Accept imperfection in early drafts. Use campus resources before you fall behind.

Recognizing Progress Over Perfection

The emotional load of academic communication is documented, researched, and shared by millions of students. It is not a sign that you do not belong. It is the predictable cost of doing intellectual work in a language your brain is still learning to automate.

Improvement takes longer than most students expect. You will not feel fluent after one semester or even one year. But you will improve. The cognitive load will decrease. The words will come faster. The gap between your ideas and your expression will narrow.

To speak English confidently in college, you do not need to sound like a native speaker. You need strategies, support, and realistic expectations. Build your network. Use practical scripts. Demand institutional resources. And remember that your multilingual perspective adds something native speakers cannot offer.

That is not a deficit. That is an asset waiting to be recognized.

How to Pay for College in 2026: Costs, Aid, and Smart Planning

How to Pay for College in 2026: Costs, Aid, and Smart Planning

The Role of Robotics in Developing Future-Ready College Students

The Role of Robotics in Developing Future-Ready College Students

Undergraduate Research: How Students Join Labs Across Campus

Undergraduate Research: How Students Join Labs Across Campus

Using AI to Succeed in College Science Courses

Using AI to Succeed in College Science Courses

What Steps Should You Take to Become a University Tutor?

What Steps Should You Take to Become a University Tutor?