Undergraduate research has transformed from a niche opportunity at elite institutions into a defining feature of quality higher education worldwide. What began with MIT's Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (UROP), founded by physicist Margaret MacVicar in 1969, has evolved into a near-universal offering. Universities across continents now recognize that hands-on research experience shapes student development in ways that classroom instruction alone cannot achieve. Today, 93% of MIT graduating seniors participate in at least one UROP during their undergraduate years, demonstrating how central research has become to the undergraduate experience at research-intensive institutions.

For international education professionals advising students navigating different higher education systems, understanding how undergraduate research functions is essential. Students who engage in mentored research develop critical thinking abilities, gain clarity about career directions, strengthen graduate school applications, and build transferable skills in communication, problem-solving, and independent inquiry. This article examines how students access these opportunities, what they actually do once they join a lab, and how undergraduate research connects to broader laboratory career pathways.

Can Undergraduates Participate in Research?

Most undergraduate students at research universities can participate in faculty-led research, regardless of major, academic year, or prior experience. Universities actively support undergraduate involvement in research projects, and students can join laboratories at virtually any point during their studies. Some begin working on research projects during their first year, while others wait until their final year before graduation.

Prior research experience is not typically required for entry-level positions. When faculty and graduate students review applications from prospective undergraduate research assistants, they prioritize genuine interest in the research topic, motivation to learn, and willingness to commit consistent time to the work. Strong grades in relevant courses can demonstrate capability and foundational knowledge, but curiosity and dedication often matter more than a perfect transcript. As researchers have noted, good performance in undergraduate coursework does not necessarily translate into lab performance, and many students discover their passion for research only after experiencing it firsthand.

Timing considerations do influence when students typically begin research. Many students start during their sophomore or junior year after completing foundational coursework that provides the scientific vocabulary and conceptual framework necessary for understanding ongoing projects. However, some laboratories actively recruit freshmen because of the return on investment: a student who joins early can be trained thoroughly and contribute meaningfully for several years. Other labs prefer students with more academic preparation. The key is matching student readiness with lab expectations.

Universities have also expanded access through course-based undergraduate research experiences, often called CUREs, which integrate authentic research directly into degree programs. Unlike traditional apprenticeship models where only a small fraction of students work with individual faculty mentors, CUREs allow entire classes to participate in asking and answering novel scientific questions. This democratization of research experience means that even students who cannot commit to extracurricular lab work can gain exposure to research methodology.

International students should be aware of additional considerations. Visa regulations may affect eligibility for paid positions, and students on F-1 visas typically need to secure Curricular Practical Training (CPT) or Optional Practical Training (OPT) authorization before accepting compensated research roles. Consulting with the international student office about compliance requirements is essential before committing to any position. Additionally, some funding programs, including most NSF Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) programs, restrict eligibility to U.S. citizens and permanent residents, so international students should investigate which opportunities welcome non-citizen applicants.

How to Ask a Professor to Join Their Research Lab

Securing a position requires effort, preparation, and persistence. Students who wait passively for opportunities to appear will likely be disappointed. Those who strategically identify potential mentors and present themselves professionally dramatically increase their chances of success.

Identifying Potential Labs

The search for a research position should begin with exploration. University department websites contain faculty profiles describing research interests, ongoing projects, and recent publications. Reading these profiles helps students identify whose work aligns with their interests. Many labs maintain dedicated websites with detailed information about current projects, lab members, and recent findings.

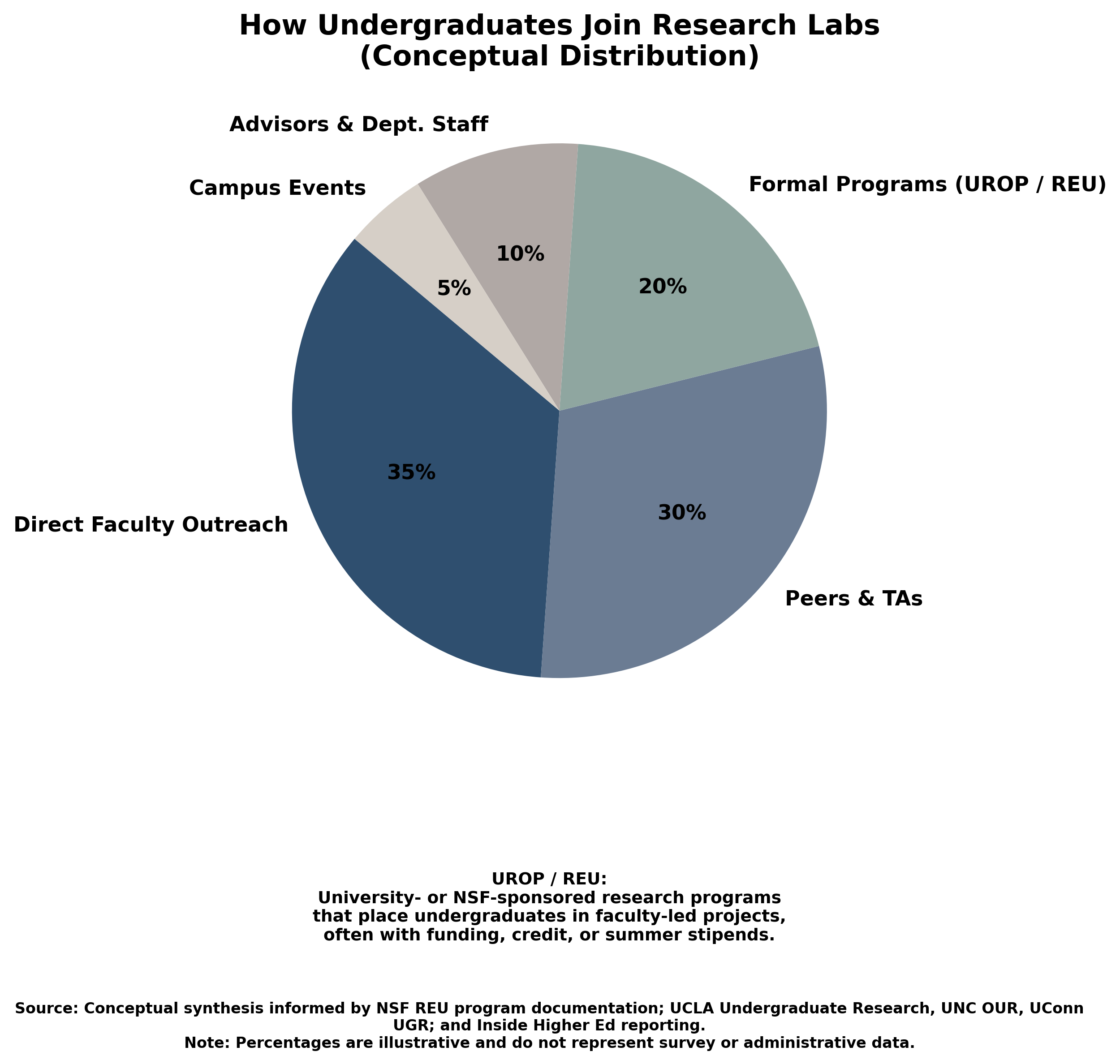

Beyond online research, students should attend department seminars, poster sessions, and undergraduate research symposia where faculty and graduate students present their work. These events provide low-stakes opportunities to learn about research happening across campus and to meet potential mentors informally. Course professors and teaching assistants often have laboratory connections and can suggest labs that match a student's interests. Graduate student TAs are particularly valuable resources because they work directly in labs and know which principal investigators are seeking undergraduate research assistants.

Networking with upperclassmen already engaged in research provides insider knowledge about lab culture, mentorship quality, and realistic expectations. Students should also utilize their university's undergraduate research office, which typically maintains databases of faculty seeking student researchers. Finally, students should not limit themselves to their home department. A biology major interested in computational approaches might find excellent opportunities in a computer science lab, and an engineering student fascinated by medical applications might thrive in a biomedical research group.

Crafting an Effective Email to a Professor About Research

The initial outreach email to a prospective faculty mentor requires careful construction. Professors receive numerous inquiries from students, so messages must be concise, personalized, and professional. Generic emails sent to multiple faculty with no customization are easily identified and typically ignored.

An effective inquiry email should open with a brief self-introduction including name, academic year, and major. The next sentences should demonstrate genuine familiarity with the professor's research, referencing specific projects or publications that sparked interest. This shows that the student has done homework rather than sending mass emails. The message should then clearly state interest in joining the lab and what the student hopes to gain from the experience. Mentioning relevant coursework and strong performance in those classes adds credibility. The email should indicate availability and expected time commitment, and close politely with an offer to provide additional materials such as a resume or unofficial transcript.

Following this structure, a student might write: "My name is Maria Chen, and I am a second-year biochemistry student. I recently read your lab's publication on protein folding mechanisms and found the computational modeling approach compelling. I completed Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry I with strong results and am eager to apply this knowledge in a research setting. I am writing to inquire whether you have openings for an undergraduate researcher beginning next semester. I can commit 12 to 15 hours weekly and am happy to provide my transcript or resume if helpful."

The Interview and Selection Process

When a professor responds positively, the next step typically involves a meeting or interview. Students should prepare by reading recent publications from the lab, even if they do not understand every detail. Demonstrating effort to engage with the research signals genuine interest.

These meetings often include conversations with graduate students and postdoctoral researchers who may serve as direct day-to-day mentors. Students should be prepared to discuss their time availability, as most labs expect 10 to 20 hours per week during academic semesters and potentially full-time commitment during summers. Asking thoughtful questions demonstrates maturity and seriousness.

Questions worth asking during a lab interview: What does the training process look like for new undergraduate researchers? What project would I work on initially? How often does the lab meet as a group? What does a typical week look like for undergraduates in this lab? What qualities make an undergraduate researcher successful here?

Students should understand that rejection often reflects lab capacity constraints rather than any deficiency in the applicant. Many excellent students contact several labs before finding a position. If an initial email receives no response, sending a polite follow-up after one to two weeks is appropriate. Persistence pays off, and students should not interpret silence or rejection as a reflection of their potential as researchers.

What Undergraduates Do in Research Labs

The daily work of undergraduate researchers evolves significantly over time. Students should enter with realistic expectations about initial responsibilities while understanding that meaningful contributions become possible with experience and dedication.

Initial Training Phase

New undergraduate researchers typically spend their first semester learning laboratory protocols, safety procedures, and equipment operation. The immediate tasks often feel unglamorous: data entry, literature searches, sample preparation, cleaning workspaces, and organizing materials. This foundational work is genuinely necessary for lab operations and provides essential context for understanding how research actually functions.

During this phase, students observe graduate students and postdocs conducting experiments, learning techniques through observation before attempting them independently. Maintaining accurate records and documentation is emphasized from the beginning, as meticulous record-keeping underpins all credible research. Students are also expected to read relevant literature to understand the broader scientific questions their lab addresses.

The key to thriving during this phase is asking questions. When assigned to process images for a study, students should ask their mentor to explain what hypothesis the images will test. When transcribing participant responses, students should inquire about the theoretical framework guiding the analysis. Transforming routine tasks into learning opportunities depends on intellectual curiosity.

Developing Competence

After initial training, typically one semester, undergraduate researchers begin running established experimental protocols with supervision. They collect and process data, maintain equipment, and contribute more directly to ongoing projects. In labs involving human subjects, undergraduates often help recruit and schedule research participants, run study sessions, and code behavioral observations.

At this stage, students begin contributing to quality control procedures and may take responsibility for specific recurring tasks. The work remains structured and supervised, but independence gradually increases as competence develops.

Advanced Contributions

Experienced undergraduate researchers who remain in a lab for multiple semesters can take ownership of specific project components. They analyze data, contribute to interpretation discussions, and present findings at lab meetings. Some assist with manuscript preparation, and sustained substantial contributions may lead to co-authorship on peer-reviewed publications.

Advanced undergraduates often mentor newer students, reinforcing their own learning while contributing to lab continuity. The most motivated students may develop independent research questions under faculty guidance, potentially resulting in honors theses or conference presentations.

Undergraduates rarely design experiments independently. Research direction is determined by principal investigators based on funded grants and established expertise. Students work within existing project frameworks, contributing to larger collaborative efforts. For this reason, the quality of mentorship matters more than the specific project. A supportive mentor who invests in student development can make any project a valuable learning experience.

Compensation, Credit, and Recognition

Undergraduate research may be unpaid, paid, or taken for academic credit, depending on institutional policies, funding availability, and individual circumstances. Understanding these options helps students make informed decisions about their research involvement.

Many introductory positions are unpaid, particularly at the beginning when students are primarily receiving training. Some universities offer hourly wages through work-study programs or direct lab funding. Summer research programs frequently provide stipends, with amounts varying from modest to substantial depending on the program. NSF Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) programs offer funded summer opportunities at institutions across the United States, though most restrict eligibility to U.S. citizens and permanent residents. International students should verify work authorization requirements before accepting any paid position.

Most universities allow students to register for research credits, typically ranging from one to four credits per semester. Some programs, particularly in engineering, require students conducting research to enroll in designated research courses. Credit may count toward elective requirements or major requirements depending on departmental policies.

Recognition for undergraduate research takes multiple forms. Students may earn authorship on peer-reviewed publications for sustained, substantial contributions. More commonly, undergraduates present posters at undergraduate research symposia or deliver oral presentations at departmental events. These experiences build communication skills and professional confidence. Perhaps most valuable for future applications is the strong letter of recommendation that emerges from a productive mentoring relationship.

These research experiences create a foundation for students considering longer-term laboratory careers, which offer varied educational pathways and salary prospects.

What to Major In to Work in a Lab

Students interested in long-term laboratory careers should understand that multiple academic pathways exist, with different educational requirements for different roles.

For clinical laboratory careers, the most direct preparation comes from majoring in Medical Laboratory Science or Clinical Laboratory Science. These programs combine scientific coursework with clinical training and prepare graduates for certification examinations. Related majors including Biology, Chemistry, Biochemistry, and Microbiology provide foundational preparation applicable across research and clinical settings. Students interested in industry positions may consider Biotechnology programs that emphasize the intersection of biology and technology. Those drawn to physical sciences research might major in Physics, Engineering, or Computer Science, while students interested in behavioral research often pursue Psychology or Neuroscience.

Educational requirements vary by career level. Laboratory technician positions typically require an associate degree or certificate in clinical laboratory science. Medical Laboratory Scientists, also called Medical Technologists, need a bachelor's degree plus clinical training and certification. In the United States, certification through the American Society for Clinical Pathology (ASCP) Board of Certification is the standard credential, and some states require additional licensure. Independent research scientist positions at universities and research institutions typically require doctoral degrees.

International students planning laboratory careers should research credential requirements in their intended country of practice early in their academic planning. Certification and licensure requirements vary significantly across national contexts, and degrees earned in one country may require additional validation for practice elsewhere.

Lab Career Salaries: Entry-Level to Highest Paid Positions

Laboratory careers offer wide salary ranges depending on education, specialization, geographic location, and experience level. Understanding this landscape helps students make informed decisions about educational investments and career trajectories.

Entry-Level Positions

At the entry level, laboratory technicians and technologists show considerable salary variation. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS, May 2024), the lowest 10 percent of clinical laboratory technologists and technicians earn approximately $38,020 per year. Entry-level hourly wages typically start around $18 to $20 per hour. Geographic location significantly affects compensation, with states like California, Massachusetts, and Alaska offering higher salaries that often correspond with higher costs of living.

Mid-Career Positions

Mid-career laboratory professionals see substantially higher earnings. The BLS reports that clinical laboratory technologists and technicians earn a median salary of $61,890 annually (May 2024 data). Laboratory supervisors average $67,000 to $83,000, and forensic scientists earn approximately $63,000 to $65,000. Experienced technologists in specialized areas can earn $80,000 to $100,000, particularly those with additional certifications.

Cytotechnologists, who specialize in analyzing cells to detect diseases like cancer, represent one of the higher-paying specializations within laboratory science, with median salaries around $97,000 according to Salary.com (2025).

Highest-Paying Laboratory Careers

The highest-paying laboratory careers require advanced education and specialization. Genetic counselors, who require master's degrees, earn a median salary of $98,910 (BLS, May 2024), with the lowest 10 percent earning $78,680 and the highest 10 percent exceeding $137,780. New genetic counseling graduates typically start around $81,000 according to the National Society of Genetic Counselors Professional Status Survey (2024). Laboratory directors and managers can earn $81,000 to over $109,000 depending on facility size and location.

Career Outlook

The career outlook for laboratory professionals remains stable. The Bureau of Labor Statistics projects 2 percent employment growth for clinical laboratory technologists and technicians from 2024 to 2034, with approximately 22,600 job openings annually. Genetic counselors show stronger growth at 9 percent for the same period, though the field is smaller with only about 300 new openings projected each year. Demand is driven by population aging and increasing diagnostic testing needs, including expanded genetic testing capabilities.

Benefits and Considerations

Undergraduate research offers career-shaping benefits but requires realistic expectations and genuine commitment.

The benefits are substantial. Research experience clarifies career interests and helps students determine whether graduate school, medical school, industry, or other paths align with their goals. The mentorship relationships built through research often prove professionally valuable for years afterward. Students develop transferable skills in critical thinking, written and oral communication, data analysis, and project management that employers across industries value. For students applying to graduate programs or medical school, meaningful research experience significantly strengthens applications.

Several considerations deserve attention. The time commitment required for productive research can conflict with demanding course loads, extracurricular activities, and employment obligations. Initial tasks may feel tedious, and students must persist through the training phase before more engaging work becomes available. Not every lab provides equal mentorship quality, and students who find themselves in unsupportive environments should feel empowered to seek alternative placements. Research requires patience; meaningful results develop over months and years rather than weeks.

Conclusion

Undergraduate research is accessible to most students at research universities who pursue it with initiative and persistence. The process of joining a lab requires effort but follows a clear path: identify potential mentors whose work sparks genuine interest, craft thoughtful outreach communications, prepare thoroughly for interviews, and demonstrate reliability and curiosity once in the lab.

The experience gained through undergraduate research, regardless of ultimate career path, develops valuable skills and perspectives that serve students throughout their professional lives. For those considering laboratory careers specifically, undergraduate research provides essential exposure to the daily realities of scientific work while building credentials for future advancement.

Education professionals supporting students across different systems should encourage early exploration of research opportunities. The investment of time and effort yields returns in intellectual development, professional preparation, and personal growth that extend far beyond any single project or publication. Whether students ultimately pursue doctoral studies, clinical careers, industry positions, or entirely different fields, the habits of mind cultivated through research remain enduringly valuable.

Which Student Apps Help You Stay Organized, Study Better, and Connect on Campus?

Which Student Apps Help You Stay Organized, Study Better, and Connect on Campus?

How Community Service Serves as Practical Training

How Community Service Serves as Practical Training

Online Study vs. Classroom Experience: Which Has Greater Impact?

Online Study vs. Classroom Experience: Which Has Greater Impact?

The Connection Between Nature, Focus, and Success for College Students

The Connection Between Nature, Focus, and Success for College Students

Campus Innovation: How Students Use AI in Coursework and Research

Campus Innovation: How Students Use AI in Coursework and Research