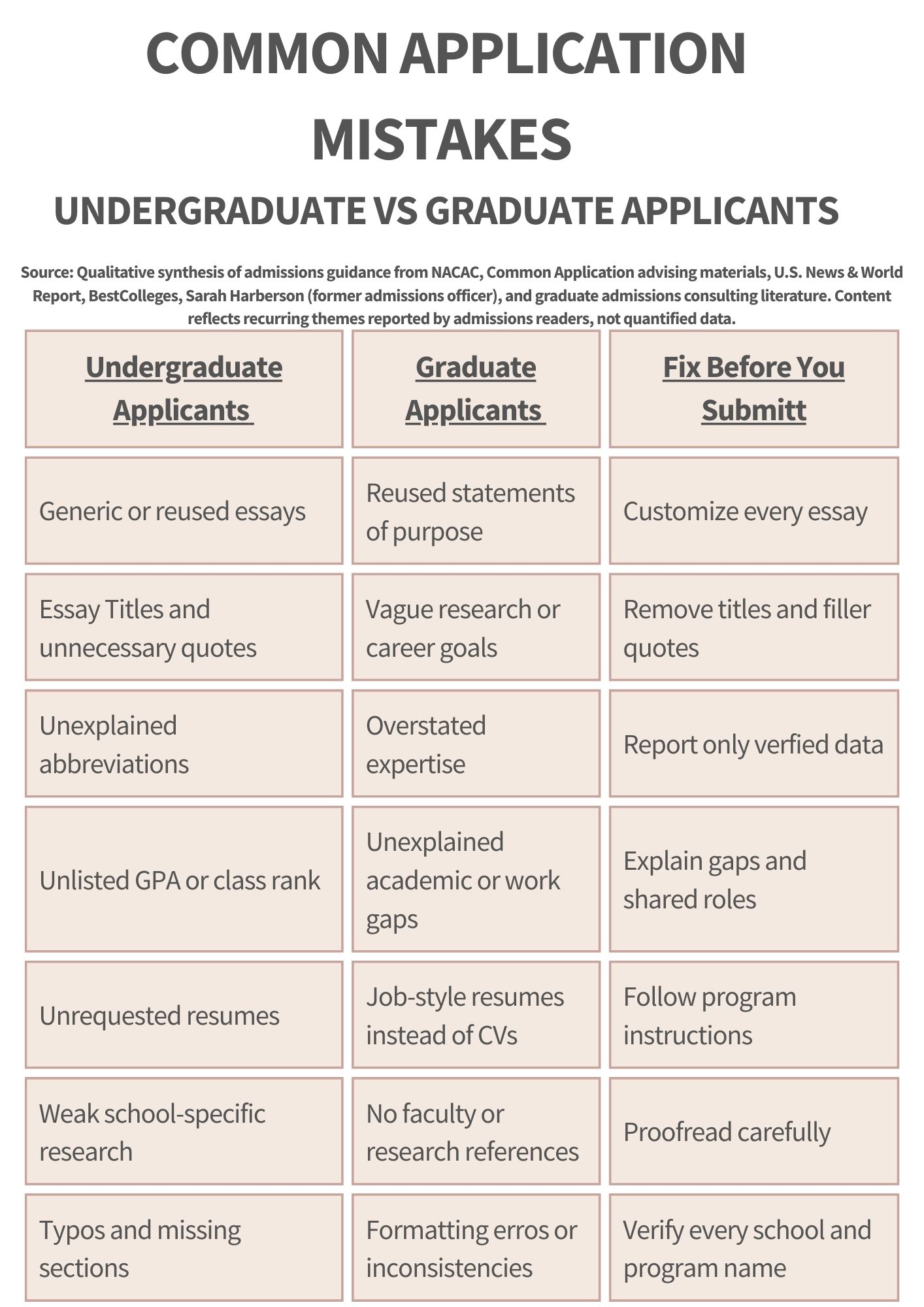

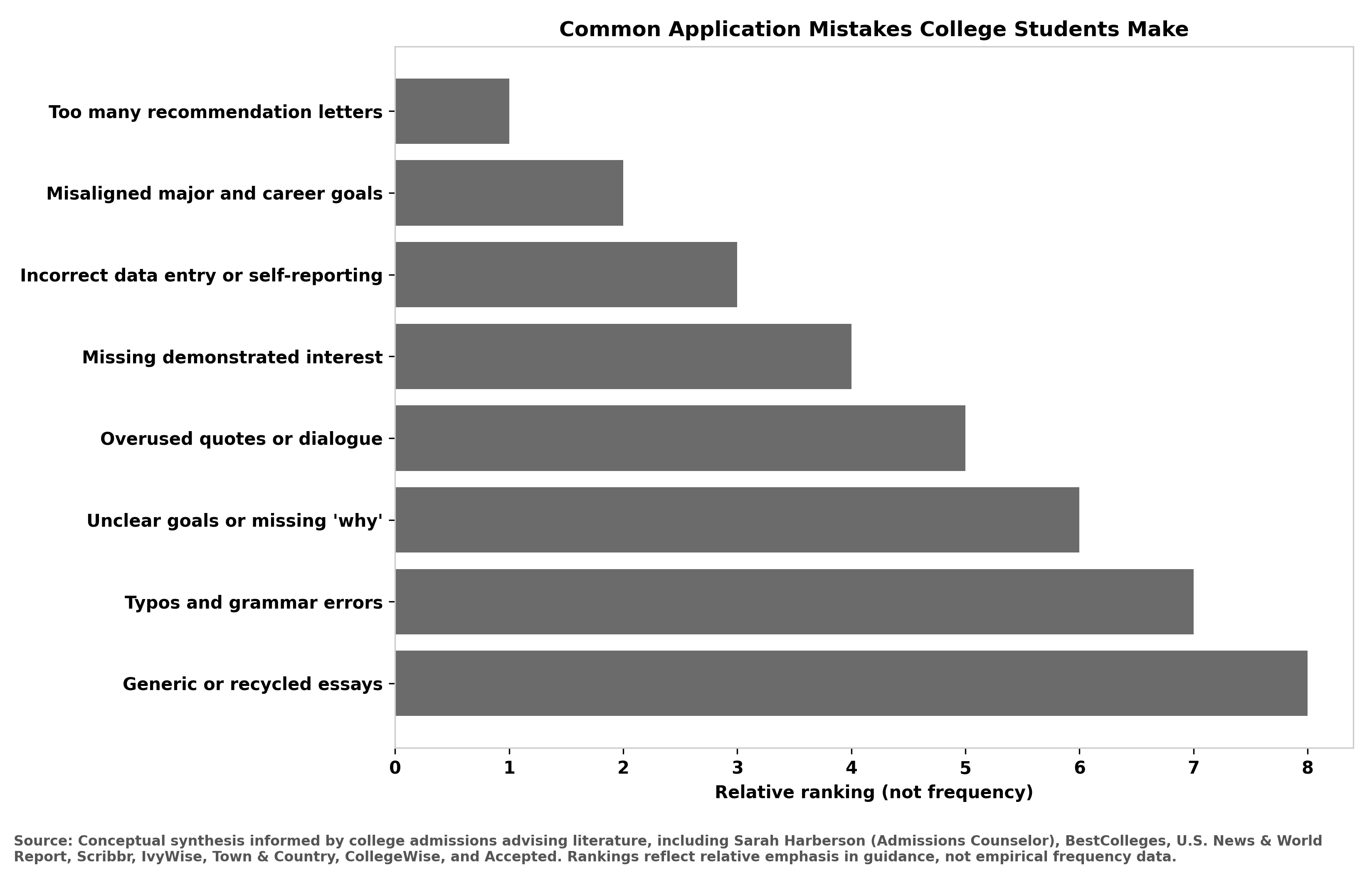

Admissions officers read thousands of applications each cycle, and small errors can push yours into the reject pile before anyone fully considers your qualifications. Whether you are a high school student applying through the Common App, a transfer student seeking a new institution, or a graduate student submitting to competitive programs, this guide helps you across the board by identifying the most common mistakes and showing you how to fix them. College application mistakes fall into predictable categories, and most are preventable with careful review.

Writing Errors That Undermine Your Essays

Skip the Headline: Why Essay Titles Waste Precious Space

Admissions officers consider essay titles unnecessary and wasteful because every character in your personal statement should serve the narrative rather than occupy space with a header the reader does not need. The admissions committee already knows they are reading your essay, so those words would be better spent on content that reveals something meaningful about who you are.

Graduate applicants face the same issue with statements of purpose because program committees want your argument and qualifications rather than a clever header that adds no substance to your candidacy. Transfer students should also skip titles and use that space to explain their motivations for changing institutions.

Let Your Voice Do the Talking: The Problem with Relying on Quotations

Starting an essay with someone else's words signals weak originality because admissions readers want to hear your thoughts rather than a famous person's take on life or success. When students lean on quotations, it often suggests they could not find their own angle on the topic or lacked confidence in their personal perspective.

If you must reference a quote, you should keep it short and make sure it had a genuine impact on your life because readers can tell when a quotation is padding rather than purposeful reflection. Graduate applicants should be especially cautious since personal statements that open with philosophical quotes often read as unfocused or pretentious to faculty reviewers.

Dialogue Overload: When Conversation Replaces Reflection

Essays heavy on dialogue miss the point of a personal statement because admissions officers want to understand how you interpret experiences rather than read a screenplay of conversations you have had. A brief exchange can illustrate a pivotal moment, but the bulk of your essay should demonstrate reflection and insight into what those experiences taught you.

Graduate applicants face a similar trap when describing research or professional moments because the committee cares less about what your supervisor said and more about what you learned from the experience and how it shaped your academic trajectory.

The Generic Trap: Essays That Could Apply Anywhere

Repurposing the same essay for multiple schools is obvious to experienced readers who can spot vague language that avoids naming specific programs or campus traditions. This approach signals low effort and suggests you are not genuinely interested in the institution. Even worse is forgetting to change the school name, which admissions officers say happens frequently and results in immediate rejection.

Transfer students must be especially careful here because your essay needs to explain why your current school is not the right fit and why the new institution is a better match. Generic language will not convince an admissions committee that you have thought seriously about the transfer.

Graduate applicants who submit identical statements of purpose to different programs make the same error and should ensure each application references specific faculty members, research groups, or curricular features that attracted them to that particular institution.

Writing What You Think They Want to Hear: The Authenticity Problem

Inauthenticity is a top admissions complaint because students who try to guess what the committee wants often produce generic and forgettable essays that blend into the thousands of other applications. Overly formal vocabulary borrowed from a thesaurus makes writing feel forced and distances you from the reader rather than creating connection.

Admissions officers can now detect AI content and essays that sound formulaic, so your authentic voice will be more compelling than polished emptiness even if your writing is imperfect. You should write about what matters to you rather than what you assume matters to them because genuine passion and honest reflection stand out in ways that calculated responses cannot replicate.

All Highlight Reel, No Depth: Essays That Only Show Your Wins

Essays that focus only on accomplishments can seem arrogant or shallow because admissions committees value self-awareness and want to see evidence that you can reflect critically on your experiences. Discussing a challenge, failure, or moment of growth often resonates more deeply than a list of victories because it demonstrates maturity and the capacity to learn from setbacks.

Transfer students have a unique opportunity here because you can discuss what you learned from your current college experience and how those lessons shaped your decision to seek a different environment. Graduate applicants should balance achievements with intellectual humility because a statement of purpose that acknowledges what you still need to learn can be more persuasive than one that oversells your expertise and leaves no room for growth.

Missing the Why: Essays Without Vision or Direction

High school applicants, transfer students, and graduate applicants all need to articulate why they are pursuing a specific path because lacking clear goals raises fit questions and makes admissions committees wonder whether you have thought seriously about your future.

For graduate programs, vague goals like "I want to learn more about this field" signal no direction and suggest you have not done the reflection necessary to succeed in advanced study. Your statement should connect past experiences to concrete future plans in a way that demonstrates you understand what the program offers and how it aligns with your trajectory.

Data Entry and Formatting Blunders

Alphabet Soup: Why Abbreviations Confuse Readers

Using abbreviations without explanation confuses readers because acronyms like NHS, FBLA, or DECA might be obvious to you, but admissions officers reviewing applications from across the country may not recognize regional or school-specific organizations. You should spell out organization names on first reference and then use the abbreviation afterward if needed.

When discussing a college's programs in supplemental essays, you should write the full name before using acronyms so that readers understand exactly what you are referencing. For example, you should spell out "Philosophy, Politics, and Economics" before referring to it as PPE in subsequent sentences.

Inventing Your Own Stats: Reporting Data That Isn't on Your Transcript

Some students input class rank or GPA when their school doesn't report it, which creates a discrepancy between the application and official documents. If your high school does not calculate or list a GPA on the official transcript, you should select "None" on the application rather than estimating or calculating your own figure. The same applies to class rank or decile rankings because you should only report what appears on your transcript.

Transfer students should be aware that college GPAs are calculated differently than high school GPAs, and you should report your grades exactly as they appear on your college transcript. Graduate applicants face a similar issue when self-reporting test scores or credentials and should stick to verified information that matches official records.

Claiming Full Credit: Not Disclosing Shared Leadership Roles

If you served as Co-Captain, Co-President, or Co-Editor-in-Chief, you must indicate that on your activity list rather than claiming sole ownership of a shared position. This kind of omission is misleading, and admissions officers may discover the truth through recommendations or social media, which would damage your credibility. Being honest about shared roles does not diminish your contribution and actually demonstrates integrity.

Score Disclosure Backfire: When Reporting AP or Test Scores Hurts You

AP scores are rarely required for admissions, but students often self-report them anyway without considering whether those scores strengthen or weaken their application. Lower scores in subjects aligned with your intended major can raise questions about your preparation, and a "3" on an AP Calculus exam when applying as a math major may hurt you at selective schools.

You should self-report only scores that strengthen your application because you control what the admissions committee sees until you enroll and send official score reports for credit.

Activities and Academics Missteps

The Resume Attachment No One Asked For

Unless a college specifically requests a resume, you should not attach one because the activity list on the Common App serves the same purpose and provides a standardized format that reviewers prefer. Adding a resume often annoys admissions officers and suggests you could not prioritize your experiences or felt the need to overcompensate for perceived weaknesses in your application.

Graduate applicants typically do need a CV or resume, but it should follow the program's format guidelines because a career-services resume designed for job applications may not work for academic admissions where different conventions apply.

Pay-to-Play Programs: Listing Other Colleges' Summer Experiences

Listing a summer program at another college on your activity list can backfire because many of these programs are seen as "pay-to-play" opportunities available to anyone who can afford tuition rather than selective experiences that demonstrate exceptional ability.

Naming another institution's program can also trigger yield protection concerns because if you attended a summer program at Harvard but are applying to Duke, the admissions office may assume Harvard is your first choice and decline to offer you a spot they expect you to turn down.

Misaligned Ambitions: When Your Major and Career Goals Contradict

Admissions officers notice when your stated major and career interests don't match because inconsistencies raise questions about your intentions and planning. If you list a liberal arts major on the college supplement but indicate "business" as your career interest on the Common App, readers may suspect you are trying to enter a competitive program through an easier path.

You should align your major choice with your stated goals or use your essays to explain the connection between seemingly disparate interests in a way that makes your trajectory coherent. Transfer students should pay close attention here because admissions committees will scrutinize whether your intended major at the new school aligns with the coursework you completed at your previous institution.

Strategic Errors That Signal Low Effort

Surface-Level Research: Showing You Don't Know the School

Displaying unfamiliarity with a college hurts your application because generic "Why Us" essays that could apply to any school signal you have not done your homework and are not genuinely interested in what makes that institution distinctive. Admissions committees track demonstrated interest, and weak essays suggest you are not serious about attending.

You should reference specific courses, research opportunities, faculty members, or campus traditions that genuinely appeal to you. Transfer students need to go further by explaining not only why the new school is attractive but also what is missing from your current institution that the transfer school provides. For graduate applicants, naming professors you want to work with and explaining why their research aligns with your interests shows genuine fit and demonstrates you understand what the program offers.

Skipping the Engagement: Not Showing Demonstrated Interest

Many schools factor demonstrated interest into admissions decisions, which means visiting campus, attending virtual events, opening emails, and engaging with admissions counselors all count toward your candidacy. Students who treat "likely" schools as backups often neglect these steps and get rejected by institutions they assumed would accept them.

Demonstrated interest matters less at large public universities and Ivy League schools, but most mid-sized and liberal arts colleges track it carefully. You should check each school's Common Data Set to see if demonstrated interest is a factor in their admissions process.

More Is Not Better: Flooding Applications with Extra Recommendations

Submitting more letters of recommendation than requested rarely helps and often hurts because extra letters slow down the review process and can signal insecurity about your application. Unless an additional recommender offers a genuinely new perspective that no other part of your application provides, you should stick to the required number.

Transfer students should seek recommendations from college professors rather than relying solely on high school teachers because admissions committees want to see how you performed in a college environment. Graduate applicants should follow the same principle because a letter from a famous person who barely knows you is less valuable than one from a professor who can speak to your work in detail and advocate for your potential with specific examples.

Presentation and Polish Failures

Typos, Grammar Errors, and the Proofreading Problem

Careless mistakes leave a poor impression and suggest you did not take the application seriously enough to review your work before submitting. Spelling errors, grammatical mistakes, and inconsistent formatting are all avoidable if you read your essays aloud, use spell check, and have someone else review your work with fresh eyes.

Graduate applicants face even higher standards because a statement of purpose with errors may disqualify you from consideration even if your qualifications are otherwise strong.

Blank Spaces and Missing Details: Leaving Out Information That Matters

Failing to complete optional sections or leaving blanks gives the committee an incomplete picture of who you are and what you have accomplished. If a college asks for information, you should assume it is helpful to your candidacy and provide it. Students who omit vital personal context like family responsibilities or work obligations may lose out to applicants who provided fuller narratives that helped readers understand their circumstances.

Your application should help the reader understand the context of your achievements, so if you worked 20 hours a week during high school or cared for siblings after school, you should include that information. Transfer students should use the additional information section to explain their reasons for transferring if the application does not provide a dedicated space for this explanation. Graduate applicants should address gaps in employment or academic performance directly because leaving questions unanswered invites negative assumptions that could have been avoided with a brief explanation.

Naming the Wrong School: The Copy-Paste Catastrophe

Writing enthusiastically about Cornell and then concluding with "That's why I want to attend Michigan" is surprisingly common, and this mistake instantly signals carelessness that can tank an otherwise strong application. You should triple-check every school name, program title, and faculty reference before submitting to ensure you have not left traces of another institution's essay in your document.

Review Before You Submit

Most application errors are preventable if you build review time into your process. Before clicking submit, you should work through this checklist to catch common mistakes:

Essays

Remove any titles from your essays

Cut quotations unless they are short and meaningful

Replace dialogue-heavy sections with reflection

Customize each essay for the specific school

Read aloud to catch awkward phrasing

Data and Forms

Spell out all abbreviations on first use

Report only GPA and class rank that appear on your transcript

Indicate shared leadership roles honestly

Self-report only strong AP or test scores

Activities

Skip the resume unless requested

Reconsider listing pay-to-play summer programs

Align your major with your stated career goals

Strategy

Research each school and reference specifics in your essays

Show demonstrated interest through visits, emails, and events

Submit only the requested number of recommendations

Polish

Proofread for spelling and grammar

Complete all optional sections

Verify every school name and program title

For Transfer Students

Explain clearly why you want to leave your current institution

Show how your completed coursework prepares you for your intended major

Obtain recommendations from college professors

Address any academic struggles at your current school honestly

For graduate applicants, the stakes may be even higher given smaller applicant pools and more scrutiny on written materials. A clean and thoughtful application signals readiness for advanced study and demonstrates you can meet the expectations of rigorous academic work.

You should start early, build in time for review, and have a trusted reader check your work because the difference between acceptance and rejection often comes down to avoidable mistakes that a second set of eyes would have caught.

Can International Students Start a Business in College? Visa Rules and Risks Explained

Can International Students Start a Business in College? Visa Rules and Risks Explained

When English Is Not Your First Language: The Emotional Load of Academic Communication

When English Is Not Your First Language: The Emotional Load of Academic Communication

How to Pay for College in 2026: Costs, Aid, and Smart Planning

How to Pay for College in 2026: Costs, Aid, and Smart Planning

The Role of Robotics in Developing Future-Ready College Students

The Role of Robotics in Developing Future-Ready College Students

Undergraduate Research: How Students Join Labs Across Campus

Undergraduate Research: How Students Join Labs Across Campus