International students contributed nearly $55 billion to the U.S. economy in 2024. The UK reports over £41 billion in economic benefit. Australia counts its international education sector as its fourth-largest export, and Canada tracks over $37 billion in annual economic activity from foreign students. These numbers prompt an uncomfortable question: who actually captures this money and who bears the real costs?

The global international education market now exceeds $200 billion annually, with nearly 7 million students pursuing higher education outside their home countries. Yet the financial flows remain deliberately opaque. Universities celebrate the revenue while downplaying their dependence on it. Governments debate immigration implications while ignoring the economic contributions. Students and their families absorb costs that extend far beyond tuition bills, often discovering the true price only after they arrive.

The money trail reveals a system designed to extract maximum value from mobile students. Universities, landlords, insurance companies, visa processors, banks, and local businesses all take their cut. Students themselves sit at the bottom of this arrangement, paying premium prices for an education that comes with restrictions their domestic classmates never face.

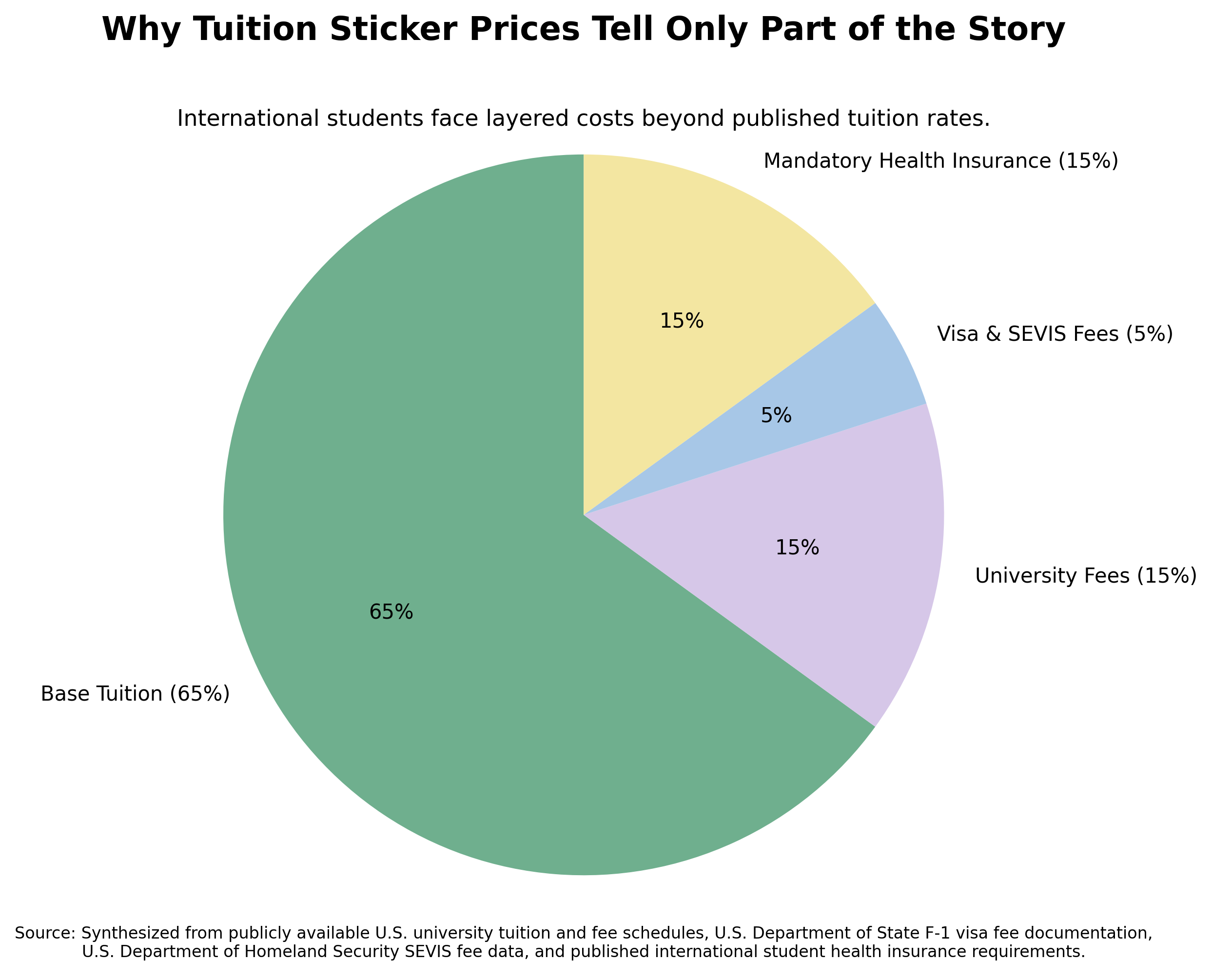

International students pay more than their domestic classmates, and this is by design. They must enroll full-time to qualify for a visa. At public universities they pay out-of-state rates regardless of how long they've lived in the area, and they cannot access federal financial aid. Most end up paying full tuition while domestic students receive discounts, grants, and subsidized loans funded partly by international student fees.

The base tuition gap is substantial and growing. At many public research universities, international undergraduates pay two to three times what in-state students pay for identical instruction. Private universities charge the same headline rate to everyone but offer far less institutional aid to international applicants. The sticker price is the real price for foreign students.

Then come the fees that universities bury in fine print. One public university lists a $250 international student fee, $120 international orientation fee, $250 records and documents fee, $286 student health fee, and a technology fee ranging from $622 to $907. These charges appear on top of base tuition. The "international student fee" is particularly cynical: a surcharge for the privilege of being foreign.

Visa costs add another layer of extraction. The F-1 student visa application fee is $160, and the visa itself costs $510. The SEVIS fee adds $350 for F-1 students. Students must pay all of these fees before boarding a plane with no guarantee of approval.

Health insurance is mandatory and expensive. Most universities require international students to carry coverage through school-sponsored plans or private insurance, with annual premiums often exceeding $2,600. Unlike domestic students who may remain on family plans until age 26, international students must purchase coverage immediately upon arrival.

Why Work Options Fall Short

F-1 students can work on campus for up to 20 hours per week during the academic year and full-time during breaks. Off-campus work requires special authorization through Curricular Practical Training or Optional Practical Training, both involving paperwork, processing time, and restrictions that limit real earning potential.

The 20-hour limit applies to total work across all jobs. A student with two part-time positions cannot work 15 hours at each, and averaging is not permitted. Working 15 hours one week and 25 the next violates the rules. Universities track payroll hours and report discrepancies to immigration officials, leaving students under constant surveillance of their work activity.

Other countries impose similar constraints. In the UK, Tier 4 visa holders can work up to 20 hours weekly during term time. Canada raised its limit to 24 hours per week, and Australia allows 48 hours per two-week period. None of these limits reflect the actual cost of living in destination cities.

The consequences of violations are devastating. Any unauthorized employment constitutes a failure to maintain status, and students found working illegally risk visa revocation and removal from the country. Even well-intentioned mistakes can end an academic career. The system offers no second chances.

A student working 20 hours at $15 per hour earns $300 weekly before taxes. In cities like New York, Boston, or San Francisco, this barely covers rent. The work limits ensure dependence on outside money while universities collect full tuition.

Expenses That Accumulate Quietly

The first month hits hardest. Flights, bedding, groceries, phone plans, and a laptop can cost $1,000 to $2,000 before classes begin. Students arrive without the household goods domestic students accumulate over years, and everything must be purchased at once, often at premium prices near campus.

Technology requirements add ongoing costs that universities rarely mention upfront. Many programs mandate specific software licenses, lab fees, or equipment not included in tuition estimates. Engineering students often need laptops costing $1,500 or more, and textbooks add hundreds per semester.

Housing poses challenges that universities do little to address. International students cluster in expensive metropolitan areas and compete for limited housing stock with domestic students and local residents. Many lack the rental history or credit scores that landlords require. Some pay several months' rent upfront while others accept substandard housing because they cannot navigate the local market.

Banking Barriers and Currency Risks

Students arrive without U.S. credit history, limiting their options for banking, housing, and phone contracts. Credit history from home doesn't transfer, and building credit from scratch takes time. The system treats international students as financial risks while gladly accepting their tuition payments.

Opening a checking account requires documentation that newly arrived students struggle to provide. Banks typically ask for a passport, visa, and I-20 form along with proof of address. Students without a Social Security Number face additional hurdles.

Sending money internationally involves multiple fees that compound silently. Banks charge for wire transfers, intermediary banks take a cut, and currency conversion adds hidden markups beyond published exchange rates. Students receiving funds from home often lose 3 to 5% of each transfer, and over four years these losses add up to thousands of dollars skimmed from family savings.

Currency fluctuations create budget uncertainty that no planning can eliminate. A student from a country with volatile currency might plan expenses at one exchange rate only to find purchasing power reduced months later.

The Price of Cultural Transition

International students face compounded difficulties as they adapt to life abroad, often for the first time and without immediate support from family and friends. Cultural adjustments, language barriers, and isolation contribute to stress. Universities recruit these students aggressively but invest little in supporting them after arrival.

The mental health burden is measurable and alarming. Research found that 59% showed depression symptoms among international first-year students and 36% showed symptoms of anxiety. These rates exceed those of domestic students facing similar academic pressures.

University counseling services consistently fall short. Many institutions lack culturally trained counselors who understand international student pressures, and wait times stretch weeks. Students from cultures where mental health carries stigma may avoid seeking help entirely.

Social isolation affects academic performance in ways institutions ignore. Loneliness is the fourth most common stressor among international students, with more than 25% reporting such feelings. Many students end up socializing primarily with compatriots, limiting the cross-cultural integration universities claim to value.

Financial stress compounds these pressures. Some students skip meals, overwork, or delay medical care, and food insecurity affects one-quarter of college students including international students facing additional barriers to assistance programs.

How Students Adapt and Cut Costs

Students from the same country or region often pool resources because institutions will not help them. They share housing, exchange job leads, and buy furniture from departing classmates. Students build support networks despite institutional indifference.

Digital tools help with financial management where universities do not. Banking apps designed for international students offer lower transfer fees and credit-building products, and services like Flywire and Convera allow students to lock in exchange rates.

Program choice increasingly reflects cost consciousness. Some students choose community colleges before transferring to four-year universities while others select regional institutions over expensive urban campuses. Shorter graduate programs reduce total expenses.

A growing number reject traditional English-speaking destinations entirely. Germany offers tuition-free public universities, and France charges modest fees. Asian institutions have improved their recruitment. The "Big Four" destinations are beginning to pay for years of treating international students as revenue sources.

Employment Created by International Students

The job creation numbers are substantial though rarely acknowledged in policy debates. International students in the U.S. supported over 355,000 jobs during the 2024-25 academic year, with one job created for every three international students enrolled. These jobs depend directly on foreign tuition.

These jobs span sectors that would suffer without international enrollment. Faculty, administrative staff, food service workers, landlords, and local retailers all benefit, and the economic activity ripples into communities that often resent the students whose spending supports local employment.

Small towns benefit alongside major cities. In Mankato, Minnesota, roughly 1,700 international students contributed $45.9 million to the local economy and supported around 190 jobs.

Benefits extend beyond direct spending. International graduates start businesses at higher rates than native-born populations, and immigrants are 42% more likely to found a business than Canadian-born individuals. Countries that restrict international graduates lose this entrepreneurial potential.

How Institutions Have Come to Rely on Foreign Enrollment

Public universities now depend on international enrollment to offset declining state funding. Research found that a 10% cut led to 16% more foreign enrollment at public research universities. When governments cut funding, universities recruit students who pay full freight. International students subsidize domestic education.

Revenue concentration has reached dangerous levels. In Australia, international student fees accounted for 26.2% of university revenue on average, and some institutions reached 30 to 40% dependence. The UK regulator warned 23 providers with high recruitment from China to develop contingency plans.

When international enrollment dropped 17% in fall 2025, some institutions faced immediate budget crises. Layoffs and program cuts followed, harming domestic students who had no idea their education depended on foreign classmates.

Competing Interests and Policy Tensions

Australia, Canada, and the UK have introduced restrictive education policies since 2023. Governments face conflicting goals they refuse to reconcile: managing immigration numbers while protecting an export industry worth tens of billions. International students absorb the contradictions.

International students have become convenient scapegoats. They've been blamed for driving up rent, using education visas for permanent residency, and squeezing out domestic applicants. Some accusations have basis in fact while many do not, but students cannot vote, making them easy targets.

The proportion staying after courses rose from 20% to half between 2019 and 2024 in the UK. Politicians cite these statistics to justify restrictions while ignoring that post-study work rights were used as recruitment tools.

Proposals to create STEM graduate pathways to permanent residency have received bipartisan support. But neither side acknowledges that universities marketed these pathways to recruit students and then governments pulled them away.

Canada has capped international student permits, and Australia proposed caps of 270,000 students. Universities warn restrictions will force layoffs harming domestic students. The warnings are accurate but self-serving. Institutions created the dependence, and now they demand students pay when politics shift.

Conclusion

The hidden economy of international students is an extraction system disguised as opportunity. Universities receive premium tuition while landlords collect inflated rent. Insurance companies sell mandatory coverage while banks charge fees at every step. Visa processors take their cut before students arrive, and local businesses benefit from spending while communities complain about the students doing the spending.

Students and their families sit at the bottom of this arrangement. They pay premium prices, navigate work restrictions designed to limit independence, manage currency risk that institutions ignore, and handle cultural transition largely alone. They are recruited aggressively, supported minimally, and blamed publicly when politics demand a scapegoat.

Destination countries face a reckoning. Years of treating international students primarily as revenue sources have created institutions dependent on foreign tuition, communities resentful of foreign presence, and policies that shift unpredictably. Students have noticed, and applications to traditional English-speaking destinations are declining.

The hidden economy generated wealth for everyone except the students themselves. That model is not sustainable. Countries that continue to extract maximum value while offering minimum support will find the pipeline drying up. The students this system depends on are not captive. They have options, and increasingly they are choosing to exercise them.

How to Pay for College in 2026: Costs, Aid, and Smart Planning

How to Pay for College in 2026: Costs, Aid, and Smart Planning

The Role of Robotics in Developing Future-Ready College Students

The Role of Robotics in Developing Future-Ready College Students

Undergraduate Research: How Students Join Labs Across Campus

Undergraduate Research: How Students Join Labs Across Campus

Using AI to Succeed in College Science Courses

Using AI to Succeed in College Science Courses

What Steps Should You Take to Become a University Tutor?

What Steps Should You Take to Become a University Tutor?