Before investing in AI, leadership must define what "value" means for your institution. Value extends beyond cost savings. It includes mission alignment, student outcomes, faculty productivity, and competitive positioning.

Different stakeholders define value differently. Faculty may prioritize tools that reduce administrative burden without compromising academic rigor. Students may want personalized support available outside office hours. Administrators may focus on enrollment yield and retention metrics. A strategic assessment must account for these varied perspectives.

Evidence from early adopters offers useful benchmarks. Georgia State University implemented an AI-powered chatbot called Pounce to improve student engagement. The system answers student queries and sends reminders about deadlines. The university reported improved enrollment retention as a result, according to Frontiers in Education research. Miami Dade College saw a 15% increase in pass rates and a 12% decrease in dropout rates after implementing AI-powered assistants, as reported by Microsoft Education. The University of Waterloo created JADA, a job aggregator digital assistant that streamlines the job search process for co-op students by matching their skills with opportunities.

These examples show measurable outcomes. They also share a common feature: each institution identified a specific problem before selecting a technology solution.

Not every AI initiative produces results. Research from the World Economic Forum indicates that 30% of enterprise generative AI projects stall due to poor data quality, inadequate risk controls, escalating costs, or unclear business value. Microsoft's 2025 AI in Education report found that 63% of education professionals say their institution lacks a vision and plan to implement AI. Enthusiasm without strategy leads to wasted resources.

Key question for boards: Can your institution articulate specific, measurable outcomes AI should produce before you invest?

Where AI Creates Efficiency and Where It Creates Risk

AI offers genuine efficiency opportunities across campus functions. It also introduces risks that demand leadership attention. A strategic assessment must map both.

Efficiency Opportunities

In teaching and learning, AI can provide personalized tutoring and adaptive learning experiences. It can assist faculty with grading objective assessments, freeing time for higher-value feedback on complex student work. It can help instructors develop lesson plans and course materials more quickly.

In administration, AI automates routine tasks in admissions, enrollment, and financial aid processing. Chatbots handle common student inquiries, reducing the volume of requests that require staff attention. Partners using AI support solutions report 20-60% reductions in total support tickets, according to LearnWise. Predictive analytics can identify at-risk students early, enabling timely intervention before academic problems escalate.

In student services, AI provides 24/7 availability for common questions. Career services offices use AI matching tools to connect students with job opportunities. Academic advising chatbots can handle routine scheduling and policy questions.

Risks That Demand Attention

Academic integrity ranks as the top concern for faculty. Research from Cengage found that 82% of higher education instructors cite academic integrity as their primary AI concern. Students can use generative AI to complete assignments, and detecting AI-generated work remains difficult. Beyond detection challenges, there is a deeper concern: students who rely heavily on AI may not develop critical thinking skills that higher education is meant to cultivate.

Data privacy and security present compliance challenges. Regulations like FERPA govern how institutions handle student information. When users enter sensitive data into public AI tools, that data may be stored, used for training, or exposed to unauthorized parties. Columbia University's AI policy explicitly warns that if generative AI is given access to personal information, the technology may not respect privacy rights required for compliance with data protection laws. Cybersecurity researchers have linked AI adoption in higher education to increased breach risks.

Output quality remains inconsistent. AI systems produce inaccuracies and fabricated information, sometimes called "hallucinations." They can reflect biases embedded in training data. Users who trust AI outputs without verification may make decisions based on flawed information.

Key question for boards: Has your institution mapped both the opportunities and the specific risks relevant to your context?

Developing Clear Policies for Staff and Students

Without clear guidelines, faculty and students make inconsistent decisions about AI use. Some instructors ban all AI tools. Others encourage extensive use. Students receive conflicting signals about what constitutes acceptable work. This inconsistency creates confusion, frustration, and enforcement problems.

Effective policy development starts with integration rather than isolation. Jisc's strategic framework for AI in higher education recommends updating existing policies on academic integrity, data governance, and acceptable use rather than creating standalone AI documents. This approach keeps rules coherent and reduces the number of policies stakeholders must track.

Some institutions have moved quickly to establish expectations. UNC-Chapel Hill now requires all undergraduate course syllabi to include an explicit AI use policy, as noted in Wiley's institutional policy research. Faculty choose from sample policy statements ranging from no AI use to conditional or full acceptance, depending on course context. This approach maintains institutional standards while preserving faculty autonomy over their classrooms.

A tiered approach to classroom use helps students understand expectations. The AI Assessment Scale, developed by researchers and highlighted by the University of Iowa, offers five levels of AI integration. These range from "No AI" for assignments where AI use is prohibited to "AI Exploration" where students are encouraged to experiment extensively. The scale does not recommend a single correct level. Instead, it encourages faculty to align AI permissions with learning goals and communicate those expectations clearly.

Staff and faculty guidelines address different concerns. These include parameters for AI use in grading, research, and administrative tasks. They specify training requirements before tool deployment. They clarify intellectual property considerations for AI-assisted work.

Policies require regular updates. AI technology evolves faster than annual review cycles. Build feedback loops with faculty and students. Communicate updates through accessible channels. Consider forming a standing committee with authority to make interim adjustments.

Key question for boards: Does your institution have a governance structure that can update AI policies as fast as the technology changes?

Assessing Costs, Benefits, and Return on Investment

AI investments require the same financial rigor applied to major capital projects. Leadership must account for direct costs, indirect costs, quantifiable benefits, and benefits that resist easy measurement.

Direct Costs

Licensing fees vary enormously. Basic tools may be free. Enterprise-level platforms with privacy protections and institutional controls can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars annually. Infrastructure upgrades add to the expense. AI systems require computing power, data storage, and network capacity that may exceed current capabilities. Training and professional development demand budget allocation. Staff cannot use tools effectively without instruction.

Indirect Costs

Implementation requires staff time for configuration, oversight, and troubleshooting. Change management takes effort. Some employees will resist new workflows or worry about job displacement. Research from the AAUP found that 38% of survey respondents said AI had led to worse outcomes for job enthusiasm at their institutions. Cultural resistance can slow adoption and reduce returns.

Quantifiable Benefits

Some benefits translate directly to budget impact. Reduced staffing needs in specific functions lower personnel costs. Improved retention rates mean more students paying tuition. Time savings for faculty and administrators can be redirected to higher-value activities.

Benefits That Resist Measurement

Other benefits matter but are harder to quantify. Enhanced student experience may improve satisfaction scores and word-of-mouth recruitment. Competitive positioning helps with enrollment in a shrinking market. Research capabilities may attract faculty and grant funding. These benefits are real but require qualitative assessment alongside financial analysis.

Building a Realistic ROI Framework

Expectations for AI returns should be grounded in evidence. Analysis from Fidelity Institutional suggests that major AI-driven productivity gains may take 10-15 years to materialize at scale, based on historical patterns of technology adoption. Short-term returns are possible in targeted applications, but institution-wide transformation takes time.

Compare your projections against peer institutions using available benchmarks. Include sensitivity analysis for different adoption scenarios. Consider what happens if implementation costs exceed estimates or if benefits take longer to materialize than planned.

Key question for boards: Are you evaluating AI investments with the same rigor applied to major capital projects?

Deciding When to Invest: A Phased Approach

Timing decisions involve genuine trade-offs. Acting quickly offers advantages. So does waiting. A phased approach can balance urgency with prudence.

The Case for Acting Now

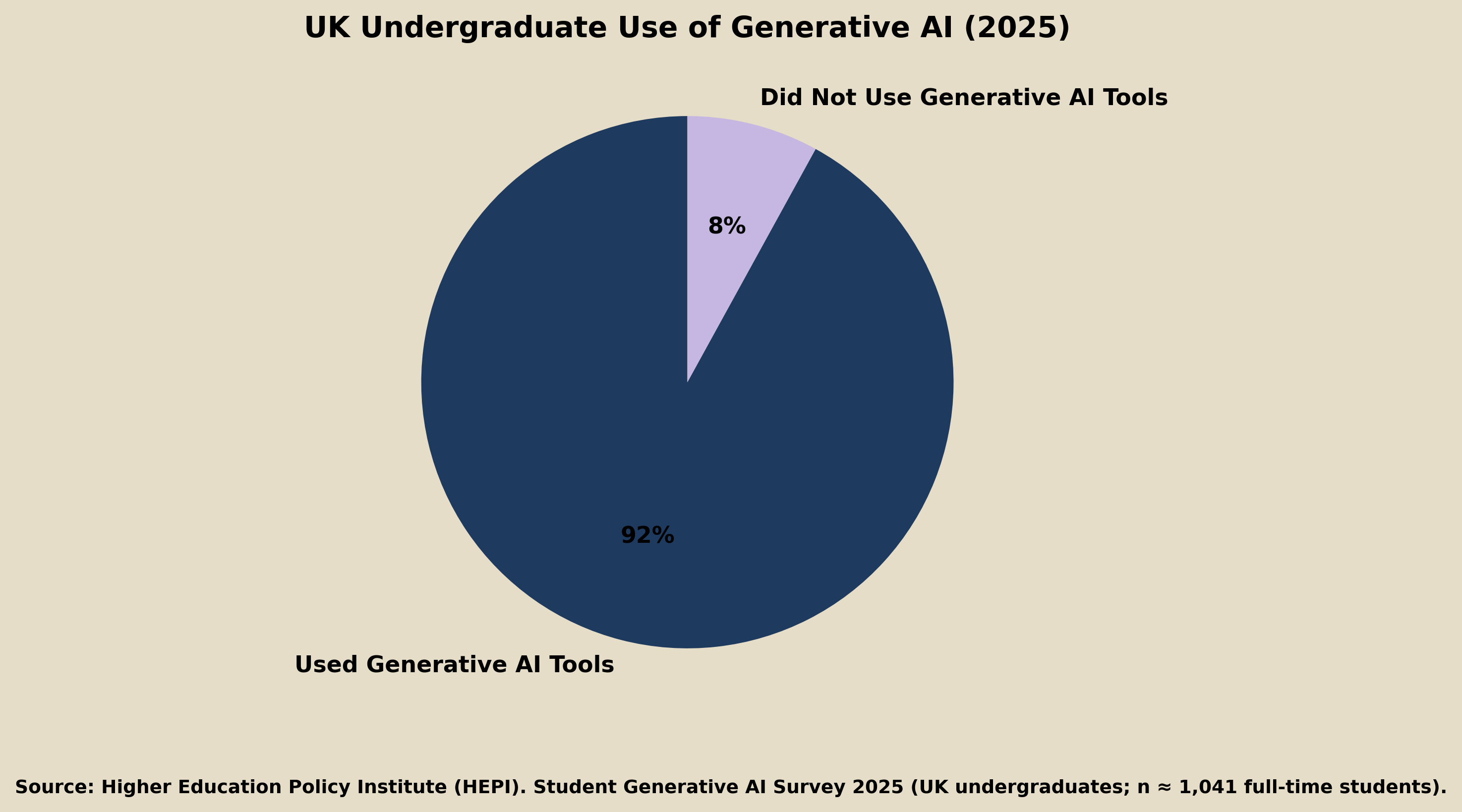

Competitor institutions are already implementing AI solutions. Students increasingly expect AI-enabled experiences. Research from the Higher Education Policy Institute found that 92% of UK undergraduates used generative AI tools in 2025, up from 66% the previous year. Institutions that delay may fall behind in recruitment and retention.

Early adoption builds institutional expertise. Staff develop skills. Data infrastructure improves. The institution learns what works in its specific context. Waiting means starting that learning process later.

Current technology is mature enough for strategic deployment in many use cases. Chatbots, writing assistants, and predictive analytics have moved beyond experimental stages.

The Case for Patience

AI technology evolves rapidly. Tools purchased today may become obsolete quickly. Waiting allows institutions to learn from early adopters' mistakes and adopt more refined solutions.

The regulatory landscape remains uncertain. New rules governing AI in education may emerge. Investments made before regulations clarify could require costly adjustments.

Your data infrastructure may need preparation. AI systems depend on clean, accessible, well-organized data. Institutions with fragmented or outdated data systems may not see returns until foundational work is complete.

A Phased Implementation Framework

A phased approach lets institutions move forward while managing risk.

Phase 1: Readiness assessment (1-3 months). Evaluate current technology infrastructure. Identify high-value, low-risk use cases. Form cross-functional oversight teams with representation from IT, academic affairs, legal, and student services.

Phase 2: Pilot programs (3-6 months). Test in contained environments. Choose one department or one student service for initial deployment. Measure outcomes against predefined metrics. Gather stakeholder feedback. UC San Diego used this approach when implementing TritonGPT. The university engaged stakeholders early, offered comprehensive training, and began with pilot programs that allowed real-time feedback before scaling, as described in Deloitte's higher education research.

Phase 3: Scaled adoption (6-12 months). Expand successful pilots to additional areas. Invest in training and infrastructure based on lessons learned. Establish ongoing evaluation processes.

Continuous: Adapt and reassess. Technology and regulations will shift. Build flexibility into your strategy. Plan for regular reviews and course corrections.

Key question for boards: Does your institution have a timeline that balances urgency with prudence?

Conclusion: A Decision Framework for Leadership

AI assessment is not a one-time decision. It is an ongoing governance responsibility. Technology will continue to evolve. Regulations will change. Institutional needs will shift. Leadership must build structures for continuous evaluation, not just initial approval.

Five questions can guide your assessment:

What specific outcomes do we expect AI to produce, and how will we measure them?

Have we mapped both opportunities and risks for our institutional context?

Do we have policies that can evolve as fast as the technology changes?

Are we applying appropriate financial rigor to AI investments?

Is our implementation timeline realistic and adaptable?

Start with cross-functional teams that include faculty, staff, IT professionals, and student representatives. Conduct formal readiness assessments. Pilot strategically before committing to large-scale deployment.

Most importantly, align every AI decision with institutional mission. Technology trends come and go. Your mission endures. The institutions that benefit most from AI will be those that use it to advance their core purpose rather than those that adopt it simply because others are doing so.

How to Pay for College in 2026: Costs, Aid, and Smart Planning

How to Pay for College in 2026: Costs, Aid, and Smart Planning

The Role of Robotics in Developing Future-Ready College Students

The Role of Robotics in Developing Future-Ready College Students

Undergraduate Research: How Students Join Labs Across Campus

Undergraduate Research: How Students Join Labs Across Campus

Using AI to Succeed in College Science Courses

Using AI to Succeed in College Science Courses

What Steps Should You Take to Become a University Tutor?

What Steps Should You Take to Become a University Tutor?