When a faculty member guides a student through a self-directed research or creative project, the relationship produces outcomes that lecture halls cannot replicate: deeper learning, stronger retention, and students who see themselves as capable contributors to their fields.

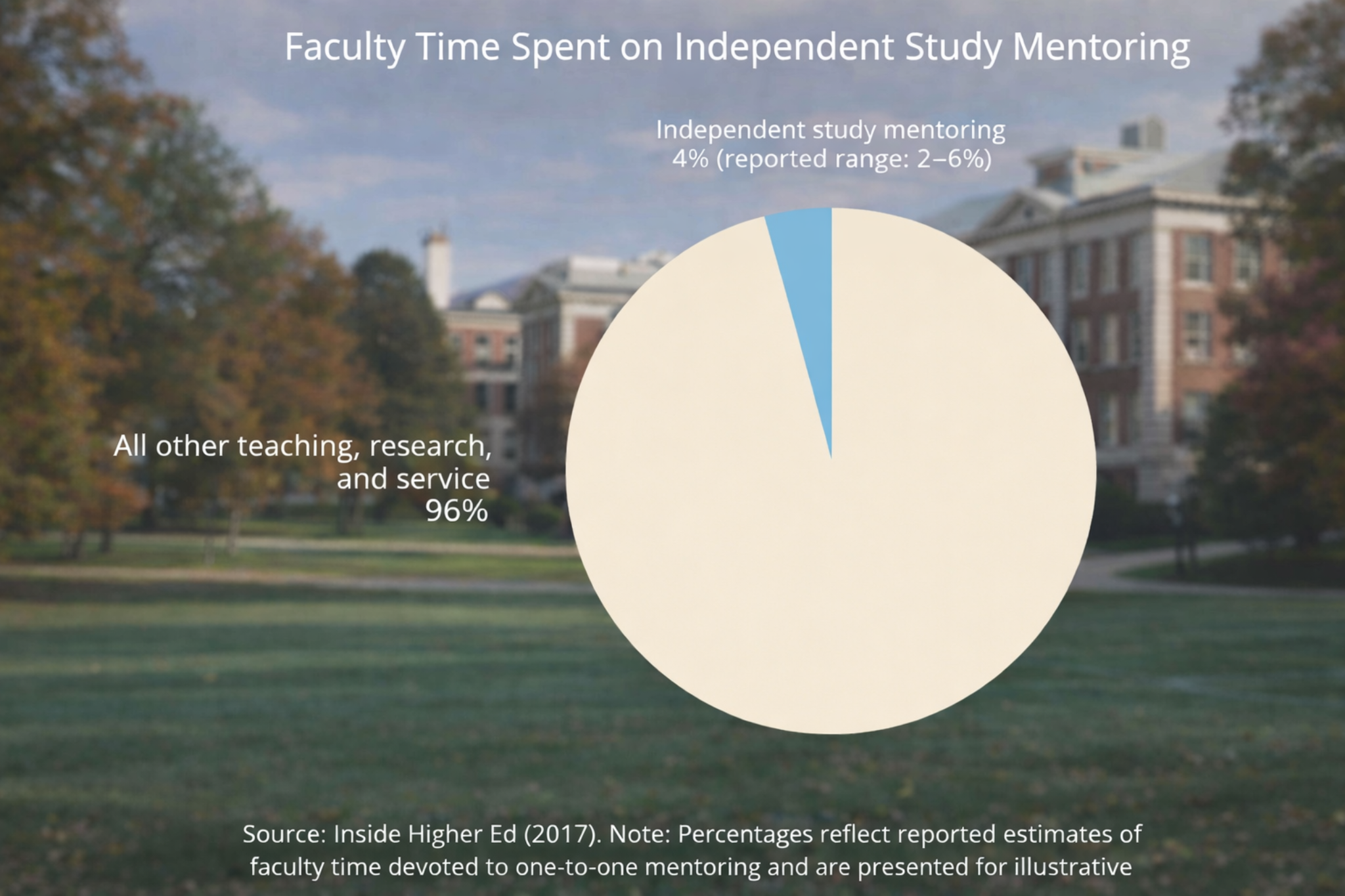

Yet faculty spend remarkably little time on this work. A 2017 analysis found professors dedicate only 2–6% of weekly hours to one-on-one student mentoring. The reasons are predictable: competing demands, unclear institutional rewards, and the labor-intensive nature of mentoring. For university leadership seeking to strengthen undergraduate research programs, understanding how faculty mentor effectively is the first step toward building systems that support this work.

What Sets Mentoring Apart from Teaching

Teaching transfers knowledge. Mentoring develops the whole person through a sustained, individualized relationship built on trust.

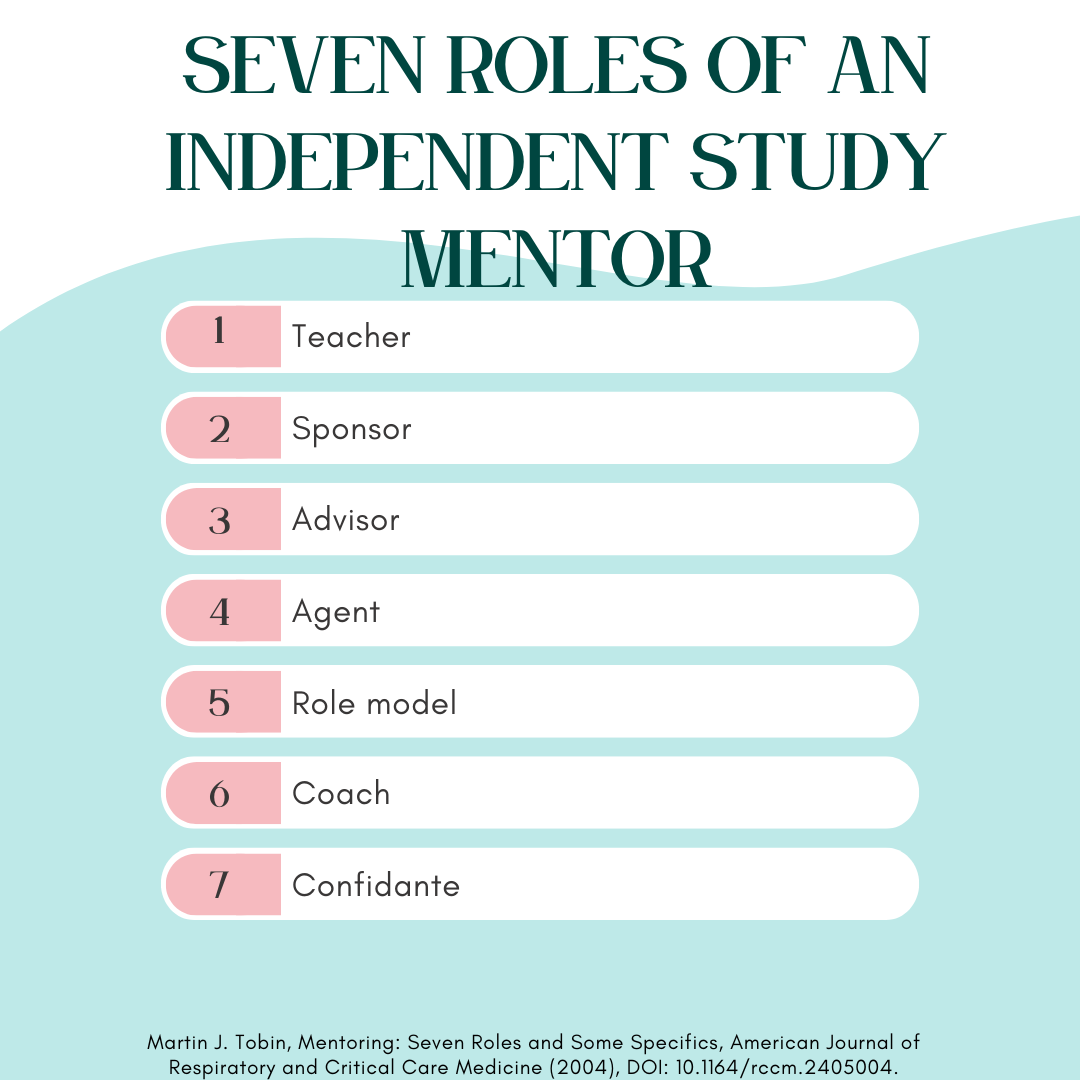

A faculty member serving as an independent study mentor fills multiple roles simultaneously. Research on academic mentoring identifies seven distinct functions: teacher, sponsor, advisor, agent, role model, coach, and confidante. This framework, established in medical education literature, remains widely cited. The mentor also sponsors students by opening doors, acts as an agent who removes obstacles, models professional conduct, and serves as a confidante for concerns students might not voice elsewhere.

This combination enables what researchers call a vicarious transfer of skills. Students don't just learn techniques — they absorb values, professional norms, and ways of thinking by watching their mentor work.

Independent study mentorship differs from course-based advising in one fundamental way: the student drives the inquiry. Faculty guide rather than direct. This demands more from mentors, who must balance structure with flexibility and know when to step back.

Establishing the Foundation: Scope, Goals, and Feasibility

The early weeks of an independent study determine whether the project succeeds or fails. Faculty invest significant time upfront to get the foundation right.

Defining project scope

Students often arrive with ideas that are too broad or too narrow. Early meetings help them refine topics into something achievable within the available time. A semester-long thesis cannot answer every question in a field — faculty help students identify a specific, manageable contribution.

The best mentors balance challenge with achievability. Research on award-winning undergraduate research mentors found their defining trait was an ability to sustain high challenge while maintaining meaningful engagement. Push too hard, and students disengage. Demand too little, and they don't grow.

Assessing feasibility

Not every good idea makes a viable project. Faculty evaluate practical constraints: lab access, data availability, equipment needs, IRB approval timelines. They consider the student's concurrent course load and outside commitments.

Honest conversations about limitations matter here. A mismatch between student expectations and faculty availability creates frustration for both parties.

Planning for setbacks

Research fails. Data doesn't cooperate. Sources prove unavailable. Effective mentors prepare students for this reality from the start.

Nobel laureate Robert Lefkowitz advises faculty to teach students to build around problems, not techniques. When students anchor their work to a question rather than a method, pivots become learning opportunities rather than failures.

Structuring the Relationship

Good intentions don't sustain a semester-long project. Structure does.

The mentoring agreement

Many institutions require formal learning contracts for independent study. These documents should specify hours per week, meeting frequency, assignments, due dates, and evaluation criteria. Written agreements protect everyone. Students know what they must deliver. Faculty know what they have committed to provide.

Meeting cadence

Regular check-ins keep projects on track. Weekly or biweekly meetings work for most independent studies, though the right frequency depends on project intensity and the student's experience level. Faculty should clarify their availability across in-person, remote, and hybrid formats early in the relationship.

Faculty should also remain accessible beyond scheduled meetings. Attributes of a mentoring relationship that consistently produce positive outcomes include planning, clear expectations, relationship building, and developing students' self-sufficiency. (Penn State URFM)

Students should arrive at meetings prepared. Requiring a brief written update or specific questions prevents sessions from drifting into unfocused conversation.

Building the timeline

Faculty and students should co-create a project timeline with interim milestones. Break large deliverables into smaller components with specific due dates. A thesis due in May needs checkpoints in January, February, March, and April. Build buffer time for the inevitable setbacks.

Frameworks for Effective Mentoring

Several evidence-based frameworks can guide faculty mentoring practice. Consistent implementation matters more than which model you choose.

The 5 C's model

The version most applicable to independent study mentorship moves through five stages: Challenges, Choices, Consequences, Creative Solutions, and Conclusions. The mentor begins by helping the student articulate their current challenge. Next, they explore available choices, then examine consequences. The creative solutions stage invites brainstorming. Finally, conclusions involve committing to a specific action.

This framework is particularly useful when students feel stuck. It provides a structured path through decision-making without the mentor simply telling the student what to do.

The seven roles in practice

The seven mentor roles don't apply equally to every project. A lab-based thesis may require more coaching on technique. A humanities project may demand more advising on source interpretation. Faculty should consciously consider which roles a particular student needs most and customize their approach accordingly.

Effective mentoring practices grounded in communication, flexibility, trust, and humility improve the chances of academic and professional success. (Springer) Effective mentors figure out which approach works for each individual, sometimes through trial and error.

Alternative approaches

Other frameworks include the 5 Pillars of Mentoring (Interest, Investment, Involvement, Inculcation, Inspiration) and the 4 C's (Connection, Clarity, Compassion, Commitment). Constellation mentoring — where students work with multiple mentors who provide different types of support — is gaining traction. Undergraduates with direct faculty interactions reported higher levels of science self-efficacy, scientific identity, and scholarly productivity than those without. (PubMed Central)

Developing Skills and Fostering Independence

Mentorship builds capabilities. The goal is a student who can work independently, not one who depends on the mentor for every decision.

Building competencies

Faculty teach discipline-specific skills: research design, writing conventions, data analysis, lab techniques. They also model professional behaviors. Students learn how to communicate with colleagues, manage time, respond to criticism, and present findings by watching their mentors work.

Moving toward autonomy

Many students feel intimidated by the word "independent." They're unsure of their instincts and hesitant to proceed without explicit permission. Helping students trust themselves is one of the most important functions a mentor performs.

The mentor's job is to make themselves progressively less necessary. Early in the project, they may provide detailed guidance. As the student demonstrates competence, oversight decreases. The mentor resists the temptation to spoonfeed, which stunts development.

When students ask "what should I do?" the mentor's response should often be "what do you think you should do, and why?"

Encouraging intellectual risk

Research requires courage. Students must be willing to pursue ideas that might not work, defend interpretations others might challenge, and accept that failure is part of the process.

Sharing your own failures helps here. Students need to know that accomplished researchers also struggled, made mistakes, and recovered.

Feedback, Evaluation, and Support

Mentoring involves ongoing assessment and emotional investment.

Effective feedback balances positive reinforcement with honest critique. Students need to know what they're doing well, not just what needs improvement. But they also need candid assessment. Kindness without honesty doesn't serve them.

Undergraduates often need longer turnaround times than graduate students. Be specific about how to improve, and offer opportunities to revise and resubmit.

Students mentored in research showed significantly higher cumulative grade point averages compared to matched peers without mentored research experiences. (CBE—Life Sciences Education) Personal connections with mentors consistently rank among the most valuable aspects of the research experience — particularly for students from underrepresented backgrounds.

Networking and Career Guidance

Mentors connect students to opportunities beyond the immediate project.

Faculty serve as conduits to others, increasing student visibility in the field. They introduce students to colleagues, recommend conferences, and help build professional networks that will serve students for years.

Career conversations belong in the mentoring relationship. What does the student want to do after graduation? Is graduate school realistic? What does a career in this field actually look like? Faculty who have navigated these paths can offer perspective students can't get elsewhere.

Encouraging students to present their research at symposia and conferences builds confidence and communication skills. It also signals that their work matters to a community beyond their campus.

Qualities of Effective Mentors

Research on successful mentoring relationships points to consistent characteristics. The National Academies' 2019 report synthesizes decades of research on what makes mentoring work.

Effective mentors demonstrate respect for students as emerging colleagues. They listen actively. They provide honest feedback. They exercise patience when progress is slow. They remain accessible. They adapt their approach to individual needs. And they share their failures alongside their successes.

Mentoring skill is learned, not innate. Programs like those from CIMER offer structured training. The Council on Undergraduate Research provides additional resources specifically for undergraduate research mentoring.

Implications for University Leadership

Institutions that want effective independent study programs must create conditions that make good mentoring possible.

Recognize and reward mentoring

If institutions evaluate faculty primarily on research output and course evaluations, faculty will deprioritize mentoring — rationally. What gets measured gets done. Tenure and promotion criteria should explicitly value mentoring contributions. Some institutions now require mentoring statements as part of the review portfolio.

Provide training

Both mentors and mentees benefit from structured preparation that sets expectations and teaches skills. CIMER's "Entering Mentoring" curriculum and similar programs offer evidence-based training. Penn State's Undergraduate Research and Fellowships Mentoring office provides discipline-specific guidance.

Allow faculty to volunteer

Reluctant mentors harm students. Those who step forward voluntarily often already possess many of the qualities that lead to success. Mandating mentoring participation typically backfires.

Set reasonable supervision limits

Faculty cannot mentor well if they're overextended. Some institutions cap independent study students per faculty member per term. UNC Chapel Hill, for example, limits faculty to two independent study students per semester in most cases.

Create exit options

When mentor-mentee relationships aren't working, both parties need a way out without recrimination. Clear reassignment policies protect students and faculty alike.

Consider co-mentoring models

Constellation mentoring distributes the mentoring burden and gives students access to varied expertise. This model is gaining traction in programs seeking to scale undergraduate research while maintaining quality.

Conclusion

Faculty mentoring in independent study combines structured guidance with adaptive, personalized support. It demands time, skill, and institutional backing. When done well, it produces graduates who have gained more than subject matter knowledge — they leave with professional identity, intellectual confidence, and relationships that shape their careers.

Faculty mentorship has the potential to increase retention of undergraduate students, particularly underrepresented minorities in STEM degrees, with mentored students more likely to continue in their field, graduate, and enroll in graduate school. (PubMed Central)

This work cannot be automated or scaled without care. It happens one student at a time. For institutions serious about undergraduate research, investing in faculty mentoring capacity is the foundation on which everything else depends.

How International Students Can Build Successful U.S. Companies on F-1 and OPT Visas

How International Students Can Build Successful U.S. Companies on F-1 and OPT Visas

Are Extension Schools Worth It? Pros, Cons, and Costs

Are Extension Schools Worth It? Pros, Cons, and Costs

Do College Career Development Programs Help Students Get Jobs?

Do College Career Development Programs Help Students Get Jobs?

How Universities Can Improve Student Engagement and Retention

How Universities Can Improve Student Engagement and Retention

From Access to Completion: How Institutions Raise First-Generation Graduation Rates

From Access to Completion: How Institutions Raise First-Generation Graduation Rates